Your First HF Antenna: A Practical Guide to Getting on the Air

Choosing your first HF antenna doesn’t have to feel like rocket science. Whether you’re limited on space, working with a tight budget, or just wondering what will actually get you on the air, the right antenna is out there. In this post, I’ll break down the key things to think about—like size, cost, simplicity, and performance—so you can find the best fit for your ham radio journey without the confusion.

ANTENNA

S21FIA

9/24/20259 min read

This blog is for you if you are starting your HF journey.

You've probably asked the classic question to your fellow HAMs: "What antenna should I get?" and received a dozen different answers from them. Don't worry—this isn't because there's some secret knowledge. It's simply because antenna selection is like choosing the right tool for a job: the best choice depends entirely on what you're trying to accomplish.

Let's bypass the confusion and help you to choose an antenna that actually works for your specific situation. But it is you who will be making the decision- nobody else can make the decision-“which Antenna is Best for you”. Consider this blog rather as a prescription, not a guideline.

The Truth

Before we dive into specific recommendations, here are some fundamental truths that will save you countless hours of frustration:

There is no such thing as a perfect antenna. Every design involves trade-offs. The goal is finding trade-offs that you can settle with.

Simple usually wins. A basic wire dipole might not look impressive, but it can work the world when conditions cooperate.

Your first antenna won't be your last. Most successful hams have tried dozens of different antennas over the years. Start somewhere and evolve.

Any antenna is better than no antenna. A "mediocre" antenna that's actually installed will always outperform the "perfect" antenna that exists only on paper.

What Really Matters: The Key Factors

Space: Your Biggest Constraint

Your available space will likely determine your antenna choice more than any other factor. Let's be realistic about what different antennas actually require:

Full-size 80m dipole: Needs about 130 feet of horizontal space

40m dipole: Requires roughly 66 feet

20m dipole: Fits in about 33 feet

Vertical antenna: Can work in spaces as small as 10x10 feet

Stealth Factor: Keeping the Peace

Sometimes the best technical solution isn't the best practical solution. For those who live in the urban or metro areas, neighbors are a big factor for raising a big size HF antenna. Consider these visibility levels:

Nearly Invisible: Thin wire antennas, especially when run through trees

Low Profile: Small verticals, magnetic loops on balconies

Obvious but Acceptable: Larger verticals, wire antennas on visible supports

Attention-Getting: Large beam antennas, tall towers

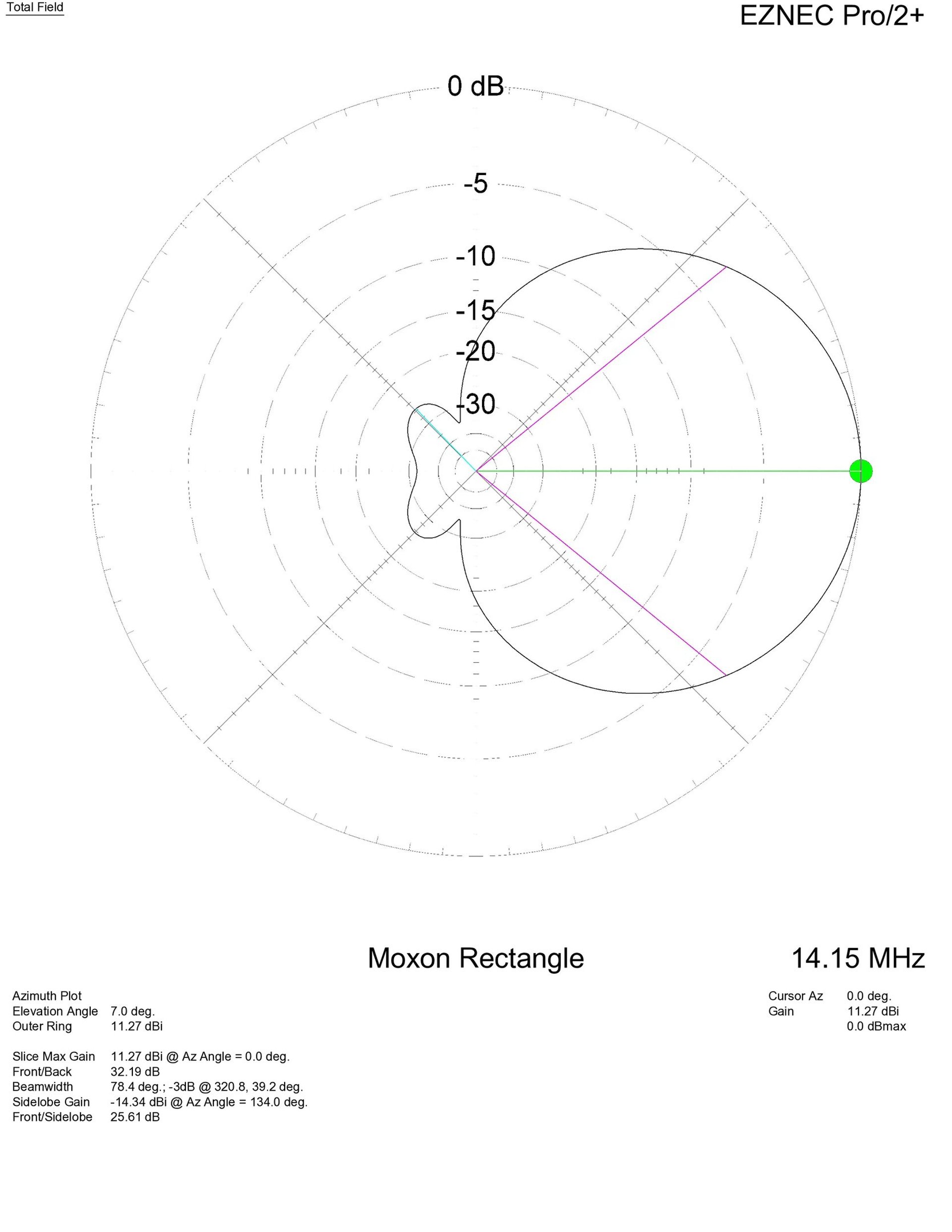

Your Operating Goals/Practices

What you want to do with your radio should drive your antenna choice accordingly:

Local/Regional Communication (0-1000 KM): Low dipoles, NVIS antennas

DX Hunting (1000+ KM): Verticals, beams, high dipoles

Contest Operation: Directional antennas, multiple antennas

Emergency Communication: Reliable, simple antennas with backup power

Popular First Antenna Options

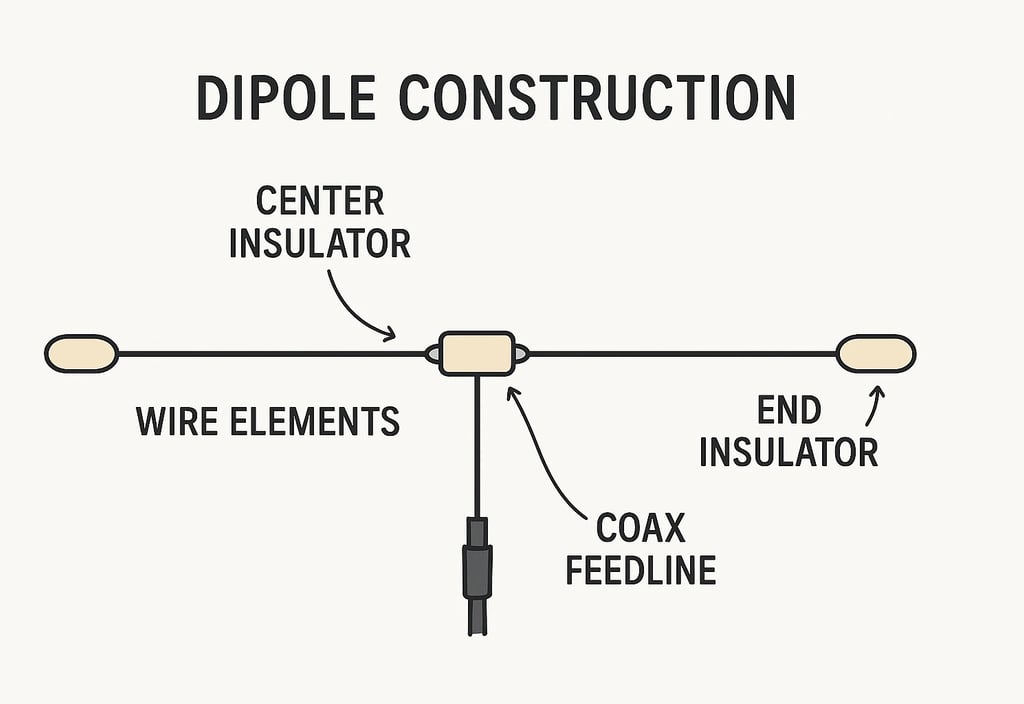

The Classic Half-Wave Dipole/ Inverted Vee

The dipole is the "Toyota/Honda" of antennas—reliable, well-understood, and effective. It gets by, may be not the best luxury/performance.

Best for: Beginners who want proven performance

Space needed: Half-wavelength of horizontal distance

Cost: from 500 to 5000 Tk.

Complexity: Low—just wire, insulators, and coax

Pros:

Simple to build and understand

Predictable performance

Inexpensive

Easy to model and optimize

Cons:

Single-band operation

Requires significant horizontal space

Performance varies with height

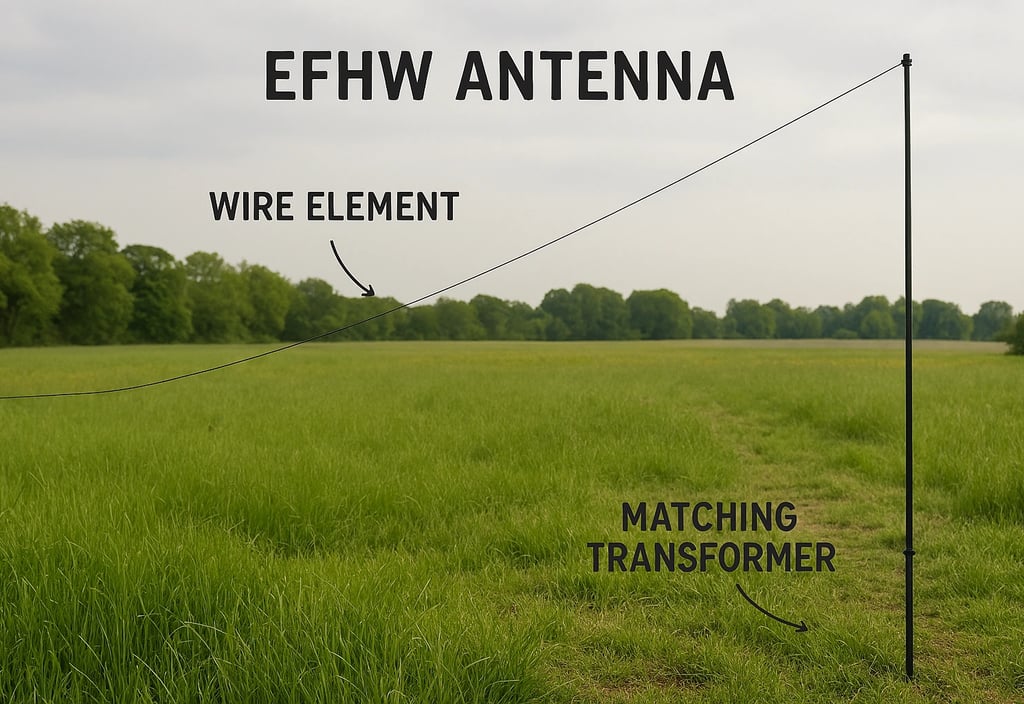

End-Fed Half-Wave (EFHW)

The EFHW is like a dipole's more flexible cousin—easier to support but sometimes trickier to tame.

Best for: Portable ops and challenging installation spaces

Space needed: Half-wavelength, but only one support point needed

Cost: from 500 to 5000 Tk.

Complexity: Medium, as it requires matching transformer (UNUN 49:1 OR 64:1)

Pros:

Only one feedpoint to deal with

Easier to support in difficult locations

Great for portable operation

Can often work multiple bands

Cons:

More sensitive to surroundings

May require careful installation to avoid RFI

Matching transformer adds complexity

Vertical Antennas

Verticals are the "pickup truck" of antennas—they excel at specific jobs, especially DX.

Best for: DX hunting and small spaces

Space needed: Small footprint, but may need radial field

Cost: 3000 – 30000 Tk. depending on design

Complexity: Medium to high as ground system is critical that directly affects the performance

Pros:

Excellent low-angle radiation for DX

Small horizontal footprint

Often work multiple bands

Less affected by nearby objects

Cons:

Require good ground system for efficiency

Can be noisy in urban environments

May need guy wires for stability

Though the antenna foot print is very small, it requires big open space for performance.

End-Fed Random Wave (EFRW)

The EFRW is like a EFHW’s cousin, this is a compromise antenna that tries to do everything reasonably well, but is not resonant to any band directly.

Best for: Portable ops and challenging installation spaces

Space needed: Not exactly but similar to half-wavelength, but only one support point needed

Cost: from 500 to 5000 Tk. For the antenna, Tuner cost is separate.

Complexity: Medium, as it requires matching transformer (UNUN 9:1) and a matching box (Tuner).

Pros:

Only one feedpoint to deal with

Easier to support in difficult locations

Great for portable operation

mostly works multiple bands

Cons:

More sensitive to surroundings

Will require careful installation to avoid RFI

Matching box i.e.- Tuner adds complexity and cost

Magnetic Loop (MAGLOOP)

Magnetic loops are the "EV/ Hybrid car" of antennas—tiny but surprisingly capable in the right circumstances.

Best for: Severely space-constrained situations

Space needed: As little as 3-4 feet diameter

Cost: 10000 to 1 lac for commercial versions

Complexity: High - requires precise tuning

Pros:

Extremely compact

Low noise reception

Apartment friendly

Directional properties useful for nulling interference

Cons:

Narrow bandwidth

Requires frequent retuning

Limited power handling

Expensive for the coverage provided

Requires careful construction for safety

MagLoop antenna of S21RC at his balcony as he was not allowed to install The Antenna on his rooftop.

Now Your Choice: A Step-by-Step Process

Step 1: Assess Your Constraints

Measure your space: Walk your property with a measurement tape. Identify possible support points for a horizontal antenna. Consider vertical options if horizontal space is limited.

Check local restrictions: Review neighbour point of view, city guidelines, and rent agreements. When in doubt, ask someone in your neighbourhood. Remember, it is better to get permission than forgiveness.

Set a realistic budget: Include not just the antenna, but coax, connectors, supports, and any matching equipment/ Tuner needed.

Step 2: Prioritize Your Needs

Which bands matter you most? If you're not sure, 20 meters is a great place to start—it's active day and long after sun down with reasonable propagation.

What's your primary interest? DXing favors different antennas than local nets.

How much complexity do you want? Be honest about your technical comfort/ capacity level and available time.

Step 3: Start Simple

For most new hams, I recommend this progression: (you are not bound to follow)

First antenna: Simple dipole or EFHW for 20 or 40 meters

Second antenna: Add another band, try a different antenna type or make a fan dipole.

Third antenna: Experiment with directional antennas or specialized designs

Installation Tips: Road to Success

Safety First:

Your Good Health is Worth More Than Any Antenna

When it comes to antenna installation, there's no such thing as being "too careful." Every year, the amateur radio community world-wide loses operators to accidents which are actually preventable. So, follow these critical safety guidelines without exception.

Never Work Alone

Accidents happen in seconds, but help might be hours away if you're working solo. A simple slip from a ladder, a sudden medical emergency, or equipment failure can turn a routine installation into a life-threatening situation.

Power Lines

Electrical contact is the leading cause of antenna-related fatalities. You don't even need to touch a power line directly, electricity can arc through the air, especially in humid conditions or when dealing with long metal antennas. As most of our Antennas are on the roof top – be aware of the power line even which is running below.

Weather considerations

Never work in wind speeds over 15 mph

Avoid installation during or immediately after rain (slippery surfaces)

Be aware that metal structures can become lightning attractors

Getting the Best Performance

Once safety is assured, focus on maximizing your antenna's effectiveness. Small improvements in installation can yield dramatic improvements in performance.

Height

Antenna height affects both your radiation pattern and your ability to clear nearby obstacles. The difference between 20 feet and 40 feet can be the difference between regional and worldwide communication.

Remember:

Higher antennas have lower radiation angles, better for DX

Each additional wavelength of height can provide 6dB or more of gain in preferred directions

Height helps clear trees, buildings, and other RF obstacles

Practical height strategies:

Trees as supports: Healthy, mature trees can support wire antennas at impressive heights

Telescoping masts: Allow you to experiment with different heights easily

Roof mounting: Can add 20-30 feet without requiring a tower

Hill placement: Natural elevation is just as good as artificial height

Point to note: Going from 10 to 30 feet makes a huge difference. Going from 100 to 120 feet makes much less of a difference. Find the sweet spot for your budget and situation.

Keep It Away from Metal

Metal objects near your antenna don't just "block" signals—they actually change your antenna's characteristics, often in unpredictable ways.

Keep antennas at least 1/4 wavelength away from large metal objects if possible

On 20 meters, that's about 16 feet; on 40 meters, it's about 33 feet

If you can't maintain separation, consider how to use metal objects as reflectors rather than fighting them

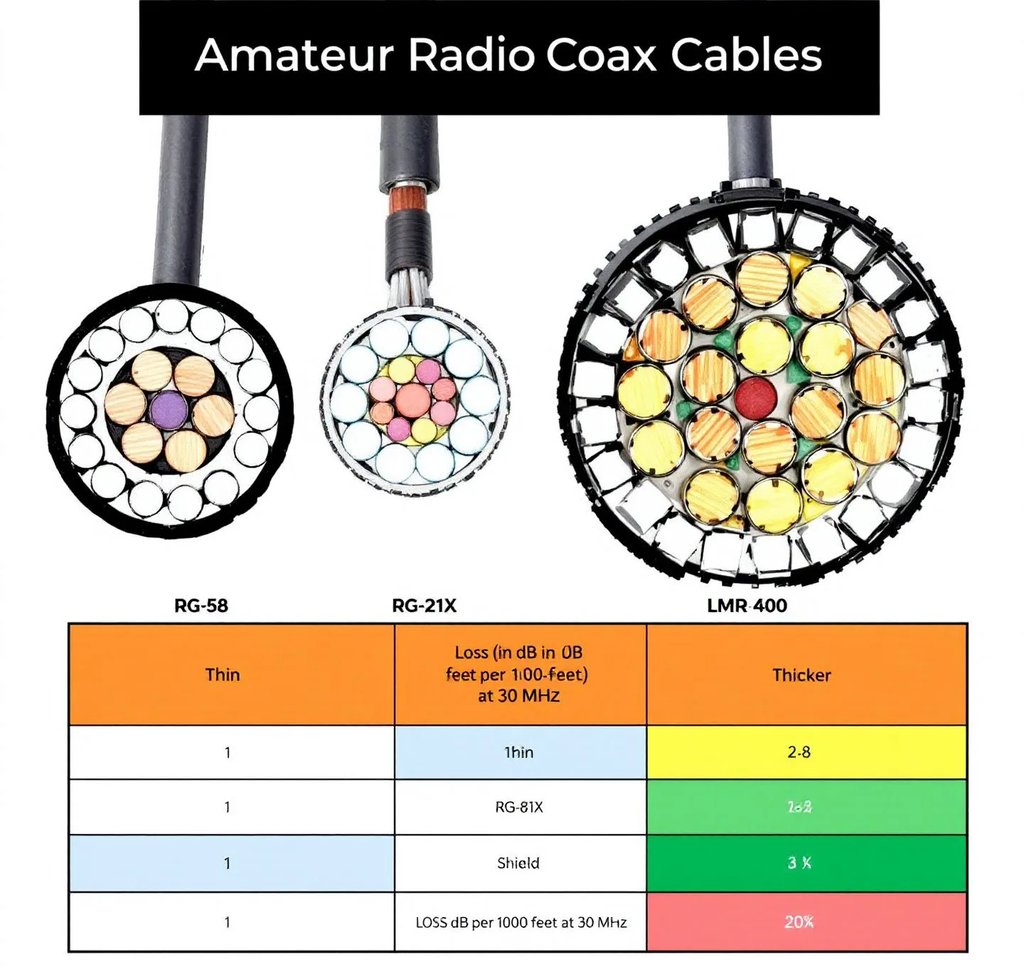

Use Quality Coax

Many hams spend hundreds on antennas, then connect them with poor quality coax that wastes half their power and degrades weak signals.

What "quality" really means:

Low loss: Look for cables with loss ratings under 2dB per 100 feet at your operating frequency

Proper impedance: 50-ohm cable for most amateur applications

Weather resistance: UV-resistant jacket, proper connector sealing

Appropriate size: Larger diameter generally means lower loss, but also higher cost and installation difficulty

Popular coax choices:

RG-8X: Inexpensive and flexible, but higher loss on longer runs

RG-213: Good balance of cost, performance, and handling

LMR-400: Excellent performance but expensive and stiff

Hardline: Ultimate performance for long runs, but requires special connectors and installation skills

Installation best practices:

Avoid sharp bends—use gentle curves with radius at least 10 times the cable diameter

Seal all outdoor connections with quality weatherproofing

Support the cable every few feet to prevent stress on connectors

Keep coax runs as short as practical—every foot of coax adds loss

Test Thoroughly

Measure Twice, Transmit Once

An antenna that looks perfect might have serious problems that only show up under measurement. Proper testing protects your equipment and ensures optimal performance.

SWR (Standing Wave Ratio): Should be under 2:1 across your operating bandwidth, preferably under 1.5:1

Resonant frequency: Where the antenna naturally wants to operate

Bandwidth: How much frequency range gives acceptable SWR

Impedance: Should be close to 50 ohms for direct coax connection

Troubleshooting common problems:

High SWR everywhere: Check connections, coax, and antenna construction

SWR varies dramatically: Look for intermittent connections or weather-related issues

Good SWR but poor performance: Check for nearby metal objects or ground system problems

Remember: These aren't just suggestions—they're the difference between a successful, safe antenna installation and a potential disaster. Take the time to do things right the first time. Your family, your neighbors, and your fellow hams are counting on you to be a responsible operator.

Common Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

Analysis Paralysis

The problem: Spending months researching instead of getting on the air

The solution: Pick something reasonable and build it. You'll learn more from one real antenna than from reading about dozens.

Ignoring Physical Constraints

The problem: Choosing an antenna that looks great on paper but won't work in your situation

The solution: Be brutally honest about your space, budget, and restrictions.

Perfectionism

The problem: Waiting for the "perfect" antenna design

The solution: Remember that a good antenna you actually build beats a perfect antenna that stays on the drawing board.

So, Your Next Steps

Measure your available space and identify support points

Choose one antenna type based on your constraints and goals

Start with a temporary installation to test the concept

Get on the air and make contacts -- this is the whole point! of all the efforts

Document what works and what doesn't for future reference

Plan your next antenna based on what you've learned

The Bottom Line

Your first HF antenna doesn't need to be perfect. It just needs to get you on the air. Today whom you see as successful ham started somewhere, usually with something simple and inexpensive. The experience you gain with your first antenna will guide better decisions for your second, third, and future antennas.

The amateur radio community is built on experimentation and learning. Don't be afraid to try something new, learn from it, and try something else. The bands are full of hams who started with simple wire antennas and went on to DXCC.

The best antenna is the one you actually build and use. Everything else is just theory.

Now stop reading about antennas and start building one. Your DXCC is waiting!

73s!!

de S21FIA/ Maruf

Get in touch

Explore

Join me on my ham radio journey.

Connect

Learn

sierra21fia@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.